By me

While not exactly a GA manufacturer – having produced only two designs fitting this category – Lockheed is nevertheless quite an interesting company to work with here, a company that’s had as many “hickups” as it had great aircraft. Never able to be classified into a single category, they’ve produced everything from ground breaking propliners like the Model 7 Vega, 8 Orion, 9 Sirius and the 10 Electra, to the incredible SR-71 Blackbird and the high-flying U-2 reconnaissance jets. And along the way, they’ve taken on the habit of proving one oft-neglected point: that you don’t have to have a legacy stretching back to the Wright Brothers to be able to produce something amazing…

Like with Burt Rutan at Scaled Composites, the driving force behind most of Lockheed’s designs from the 30s onward was a brilliant engineer, the famous Clarence “Kelly” Johnson. A man well versed in thinking outside the box, he was quick to adapt to any requirement put before him, a skill that earned him one of the most fascinating design lists in the history of aviation:

- the model 10 Electra and 12 Electra Junior

- the PV-1 Ventura light bomber based on the L-18 Lodestar transport (itself derived from the Electras) which was the mainstay of the UK’s maritime air defense at the beginning of WW2

- the highly-innovative P-38 Lightning

- the stunning Constellation airliner, one of the most graceful propliners to ever fly

- the P-80 (later F-80) Shooting Star, America’s first combat-capable jet fighter, and it’s trainer version, the popular T-33

- the pocket-rocket F-104 Starfighter

- the still-speed-record-holding SR-71 Blackbird

- the high-flying U-2

- a plane that needs no introduction, the C-130 Hercules, still holding the record for the longest uninterrupted production run, coming up to 57 years!

- the pioneering F-117 Nighthawk

- and the now-mostly-forgotten L-1329 JetStar

1. Change of priorities ahead…

The first to get the ball rolling on Lockheed’s reputation was the P-38. Up until the late 30s, Lockheed had been mostly known for its civilian aircraft – or rather the records they set in the hands of pilots such as Amelia Earhart and Wiley Post. The closest they came to making a military aircraft was the Ventura, which was still a tried-and-tested civil design converted – in very little time – into a light bomber and coastal patrol aircraft. So when the USAAF in 1937 invited Lockheed to submit a proposal for a fast-climbing interceptor, many observers were not very optimistic – especially since the inexperienced company would be going up against companies such as Curtiss, Douglas and North American which had far more experience in the field.

However, that very inexperience is probably what gave Lockheed the edge. Unencumbured by the muscle-memory of years of building fighters, the team led by H.L. Hibbard – of which Johnson was a member – was able to take a more objective look at the requirement and think outside the box. The result left no one cold; the P-38 was a stunner any way you looked at it. Among all of its achievements, it was also the first US tricycle fighter, and the first US aircraft to down an enemy plane during WW2, a German Focke-Wulf FW.200 Condor patrolling off Iceland. Aggregated at the end of the war, it was one of the most successful – if not THE most successful – twin-engined fighter and became famous as the aircraft flown by Antoine de Saint-Exupery on his last flight off the coast of Sicily.

2. 4 engines 4 long haul?

Despite the fact that by war’s end the needs of the moment had turned Lockheed – like many other companies – into a purely military manufacturer (with even the nascent Constellation being hurriedly pressed into military service as the C-69), there were a number of farsighted people who were still keeping tabs on what was going on behind their backs in the civil world. And soon enough, when the post-war economy recovered in the mid 50s, Kelly Johnson’s team at the celebrated Skunk Works came to the conclusion that the time was right to try out their luck in the emerging business aviation segment.

Up until that time, the serious “transcontinental businessman” had very few suitable aircraft to choose from – indeed, most where whirling about in converted medium bombers such as the North American B-25 Mitchell or the Douglas A-26 Invaider (an even larger stuff like the Douglas B-23 Dragon), dirt cheap and dumped en masse onto the civil market after the hostilities had ended. The light tourer sector didn’t offer much hope either – even a high-end piston twin would be arduous on a flight across the US, with frequent fuel stops and all the associated hassle; not to mention lumbering down low in the worst of the weather.

No, what was needed was something new, something modern, something specifically tailored for the role. A fast, high-flying jet. Drawing on their extensive early experience with the P-80 – the Korean War having just finished – Johnson’s team decided on an aircraft that would become the template for the modern business jet: a twin-engined 10 seater turbojet with swept wings, christened the JetStar :).

Powered by two British Bristol-Siddeley Orpheus turbojets, the JetStar was almost a revolution. The first pure bizjet, designed and built as such, it had represented a giant leap from the civilianized bombers that were plowing the medium flight levels at the time. With a swept-back wing (at 30 degrees), it had promised to be fast and it’s metallic, pointy appearance was just screaming “progress”.

Inevitably though, there was a problem. To simplify production and keep costs down, Lockheed had tried negotiating with Bristol-Siddeley to license-produce the Orpheus in the US, much like Allison did with the Rolls-Royce Merlin during WW2. The negotiations had failed however, which left Lockheed with only two pairs of engines powering the two prototypes – the only four Oprheus engines ever made at that point – which wasn’t really enough to make progress. There was no engine yet available in the US with the Orpheus’ combination of size and power, so Johnson – in his typical display of lateral thinking – decided he’d simply have stick more engines on. How hard could it be? 😀

Apparently not very 🙂 – the second prototype soon flew again with four Pratt & Whitney JT12 turbojets, grouped in the back in a configuration that would be adopted – and made famous – by the much more well known Vickers VC.10 and Ilyushin Il-62 airliners five and six years later respectively.

While not technologically as advanced as the previously-featured Starship (in relative terms), the JetStar did take non-commercial aircraft to a whole new level. The design included backups of every major system analogous to those found on commercial airliners – a huge novelty in the simple and uncomplicated world of light aviation – while it’s cockpit was a meeting place for the most advanced navigation and instrumentation technologies available at the time, far, far removed from even the best tourers. Indeed, some reports indicate that it took six months to train pilots to think and act fast enough for the speedy and complex JetStar!

The JetStar did have one other claim to fame that made up for it’s relatively conventional design: it was the first, and so far only, four-engine bizjet to see production (but not the only one designed as such, with the abortive McDonnell 119/220 – to be featured here soon 🙂 – flying in prototype form only), and was for a long time the largest bizjet available on the market. Coupled with its hefty weight – 19.2 tons – and four thirsty engines, it naturally drank a lot of fuel, so the optional slipper tanks were quietly added as standard equipment. Despite the high consumption, it could do 4500 km in a stretch, which was nearly intercontinental range – quite a rarity among bizjets for some time to come.

JetStar cockpit & closeup of the center pedestal @ Airliners.net

3. You ain’t nothing but a Hound Dog:

As well as aiming for the business market, during the design phase Lockheed was also eying a potentially-lucrative USAF contract for a Utility Transport Category aircraft under the Utility Cargo Experimental (UCX) program. To this end they developed the C-140, generally similar to the basic civilian JetStar, which they pitched to the USAF as a multipurpose fast jet transport (probably with a “four engined safety for your bureaucrats” tag line). All was fine and well – right up until the contract was canceled due to budget cuts after just 16 examples were delivered…

USAF Air Force Communications Service C-140A @ Airliners.net

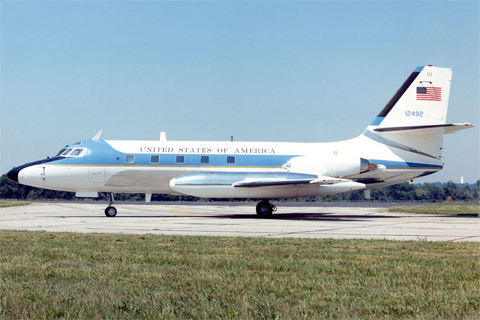

Though few in numbers, the C-140’s Vietnam service record – including auxiliary communications roles back home – was further augmented by the VC-140B. Like all V-prefixed aircraft in the USAF, the VC-140B was a VVIP version, several times also acting as the famous “Air Force One” when transporting the President and his entourage on shorter distances.

Beautifully restored VC-140B @ Airliners.net

However, while the C-140s were transporting the President, a civilian JetStar had the honor of transporting the King! 🙂 “Hound Dog II” was one of the two aircraft owned by Elvis Presley, along with his prized Convair CV-880 “Lisa Marie”. Bought for nearly $900.000 – at the time, quite a lot! – while waiting for the CV-880 to be delivered (which had in turn cost less), N777EP apparently didn’t have a long service life and is today beautifully preserved as part of an exhibit at Graceland (more photos here).

4. Louder than Elvis:

Yet, the JetStar’s range and hauling capacity came at a – for the then 70s – great price. The oil crisis meant that filling the thirsty jet up was becoming quite expensive, especially now that more modern twin- and tri-jets like the Canadair Challenger and Dassault Falcon 50 were only inches away from first flight. While some wealthier owners could live with this until the crisis had ended, the nail in the original JetStar’s coffin was – noise. Four small whining turbojets did little to make the JetStar a neighbour-friendly aircraft, so in the face of operational restrictions, a decision was made in the mid-70s to re-engine it with quieter and more economical turbofans.

The engine chosen was the then-new Garrett TFE731 introduced in 1972, which would go on to power a number of highly-successful business jets – including the Falcon 50, the nearest thing the JetStar had to an equal competitor at the time.

Unusually – what was usual about the JetStar anyway? – the first step was not to produce a “new and improved” version, but retrofit existing JetStars, which then became known as the 731 JetStar to differentiate them from the unmodified – and renamed – JetStar I aircraft.

As is to be expected, the new engines breathed new life into the design, giving significantly better performance (especially at lower altitudes) and maximum takeoff weight, greatly reduced noise – and of a less-irritating pitch as well – and increased range; with maximum payload (a full cabin) the 731 could do 4800 km in a stretch, while sacrificing some passengers for full fuel tanks, it would be touching 5200 km, a 15% increase over the old model. This translated into some interesting operational capabilities – even with a full cabin, the 731 could comfortably hop over the Pond between destinations such as Gander in Canada and Shannon in Ireland; and its four engines meant it could go there along shorter routes, not hugging Greenland and Iceland for fear of losing an engine (which could all in all – according to the Great Circle Mapper – save almost 1000 km!).

A very welcome upgrade for JetStar owners, the 731 mod was a great success and – the 731s being retrofits and not new-built aircraft – inevitably ended up being integrated into the production line, creating the brand-new JetStar II, of which only 40 were ever produced.

5. Headin’ south over the border…

Despite the increased grunt that gave the JetStar II comparable performance to most modern business jets in its class, the end for this fascinating design was in sight even before the decade was out. In the end it wasn’t age that killed it, but to an extent, I’m inclined to believe Kelly Johnson’s, own outside-the-box methods. Conceived in the gas-guzzling late 50s, when jet engines were just getting into their stride, the JetStar was becoming rapidly outdated in the late 70s. Jet engine technology, already increasing by leaps and bounds, had started producing engines that had more output than the two TFE731s combined, burned less fuel and were easier to service, with longer service lives. In this environment, the JetStar’s four maintenance-intensive engines were starting to become over-redundant. The end didn’t take long to come and in 1979, after the 40 JetStar IIs were produced – for a grand total of 204 (206 according to some sources, probably including the two prototypes) – Lockheed pulled the plug on this design…

Thankfully though, like the Starship, the JetStar did not go out quietly. A number are still happily flying, with the majority operating in the Mecca of vintage bizjets – Mexico :). This country is fascinating as a whole, but when aviation is concerned, it is completely off the scale! A country where Sabreliners, 20 series Learjets, Starships, early Candair Challengers and Dassault Falcons are the order of the day is, you must admit, the perfect home for the JetStar… it could almost be lost in the variety :D. With the country’s relatively lax noise rules permitting more-or-less regular operations of turbojets, Mexico is home to all three variants of the JetStar, including:

- JetStar I of the Mexico Government (classy!): photo 1 and photo 2 @ Airliners.net

- 731 JetStar in not the most flattering state (the only photo I could find) @ Airliners.net

- JetStar II, one of several on the Mex register, photo @ Airliners.net

The remainder – all JetStar IIs, Is being banned from many noise-sensitive airports – are mostly registered in the US, while there are also quite a few interesting ones out in the big wide world :)…

- 5-9003 used by the Iranian Air Force, photo @ Airliners.net

- 9G-ABF flying in Ghana, photo @ Airliners.net

- HB-JGK registered in Switzerland, photo @ Airliners.net

- TC-SSS and TC-NOA looking beautiful together, photo @ Airliners.net

- VP-CSM registered in the Virgin Islands, photo @ Airliners.net

- ZS-ICC based in South Africa, photo @ Airliners.net

“the only four Oprheus engines ever made!”

That might be a surprise to the operators of all those Folland Gnat, Fiat G91s and Fuji T-1s!

Orpheus production actually amounted to several thousand and was license-built in India and Japan.